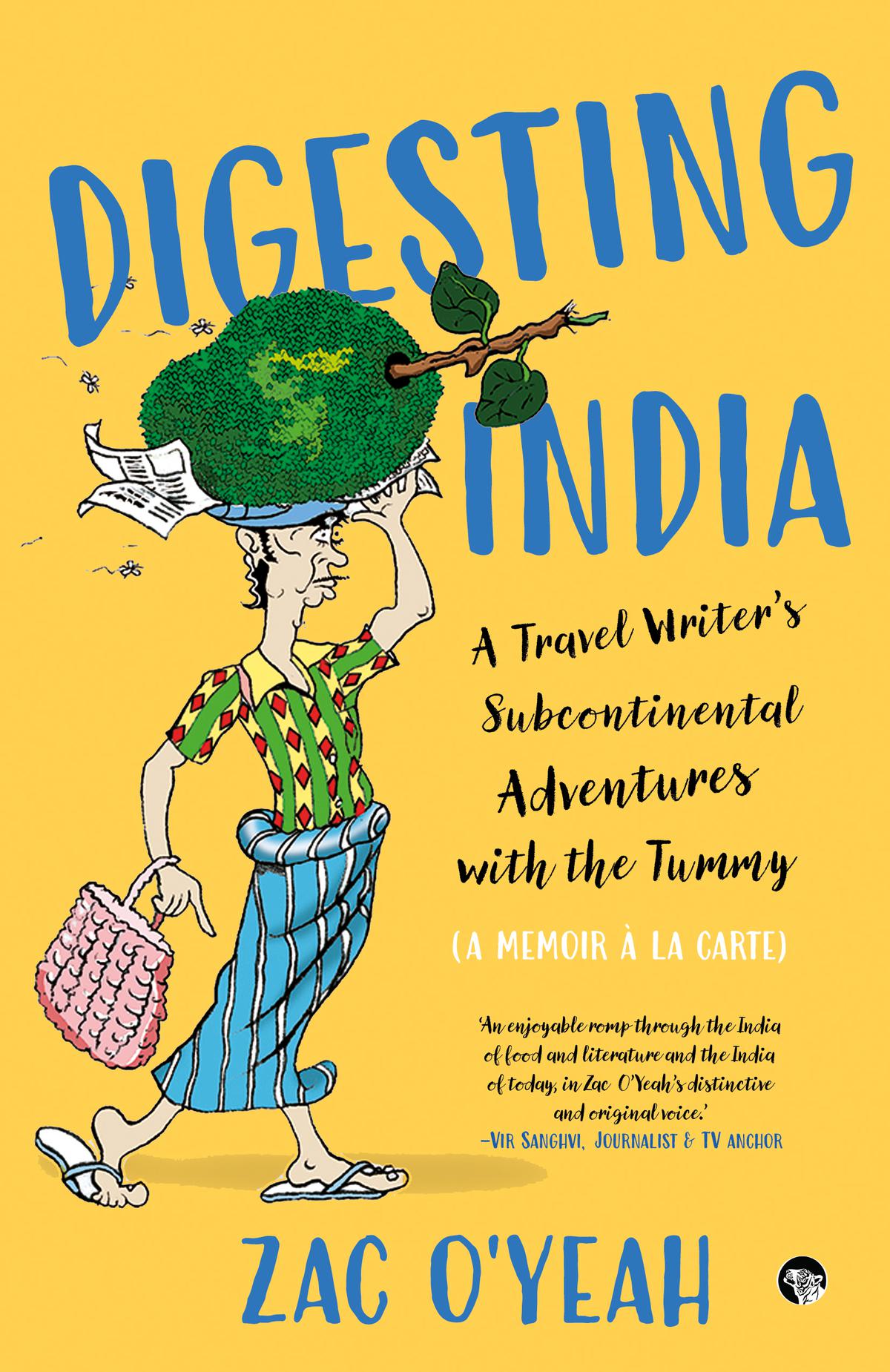

Zac O’Yeah looks back at his 25-odd years as a travel writer in his book ‘Digesting India’.

| Photo Credit: Anjum Hasan

Eating for a living is a serious danger,” says Zac O’Yeah, Bengaluru-based travel writer and novelist of Swedish origin. His latest book, Digesting India, is a testament to how lethal this exercise can be on one’s innards. “I travel with aspirin, imodium and antacids,” he says. “But even that doesn’t always save you.”

Part memoir, part travelogue with lashings of history, literary references and unbridled fun, this collection of eight essays takes the reader on a whirlwind ride through India and the food (and alcohol) it holds. From a rather beer-sozzled traipse through Bengaluru’s colonial history to a (very) brief brush with asceticism at the Gandhi Sevagram Ashram in Maharashtra, a glimpse into the highly-cosmopolitan cuisine cultures of New Delhi and Goa and detailed descriptions of dubious dives, dangerous curries and deadly lavatory experiences, Digesting India will leave you chortling and hungering for more. Edited excerpts from an interview:

A lot of the book feels very retrospective, looking back at those 25-odd years spent as a travel writer. You’ve said in the prologue that it is a pandemic baby of sorts, written when travel and food culture felt irretrievably changed.

When the pandemic started, I had just got back from Italy where I went in 2019; later, it was discovered in autopsies that people had COVID-19 there already then. I was supposed to go to Hollywood for work in early 2020 but all this news of the pandemic made me drag my feet, which in a sense is lucky because if I had gone, I would have been stuck there for months. I’d probably be sleeping on a park bench since the employers only gave a freebie week in hotels. And get arrested for vagrancy. So, from a travel-writing point-of-view, it was a major disruption.

One can remain cheerful for a bit and write up recent travel experiences. But then as one runs out of stories, what does one do? I decided to spend the lockdown thinking through what I had done in the past and if there was any ‘red thread’. I’ve written about many things such as cultural heritage and historical monuments, but it struck me that more than anything else, I’ve been obsessed with finding good food. So that’s where it began. I realised that my life had been a great food adventure through the cuisines of India and then I figured it might be something worth writing about.

What kind of research has gone into this collection of essays, which forces a reader to see food as an intellectual and cultural experience as well?

Somebody once told me that in India if you travel a hundred kilometres, the food will be completely different from the previous town. So, in my book, I look at just this. I travel and then I eat, and I’m in a new paradise. And what that paradise is about is often some interesting history behind its food.

In Tamil Nadu, for instance, you can go to any place in the Kongu Nadu region, which is the heart of the State, and find gourmet dishes that are probably cooked the same way today as millennia ago. Then you move on to Puducherry and you’ll find dishes that blend French colonial and Tamil influences into some kind of haute cuisine.

You mention travelling across India in the 90s and the pitstop in Bengaluru that made you a novelist thanks to “a little luck, and much cheap beer”. Tell us more.

I got off the train in Bengaluru thinking I’ll figure out where to go next. Then I just decided, why leave? I stayed for one or two months in a lodge in Majestic and felt very much at home there. The town is full of bookshops and good restaurants, so in my mind, I thought I was in heaven; no need to die to go to heaven, just stay in Bengaluru and avoid getting smashed by a drunk driver.

As time went by, I settled down permanently in the city, and started noticing that there was not much city fiction. A writer friend, Ashok Banker, told me his ambition was to expand the shelf of Mumbai novels. So, I thought maybe I could do something like that to Bengaluru fiction and started that very ambitious Majestic Trilogy, which took me 10 years to write.

You talk about your visit to the Gandhi Sevagram Ashram and the food you sampled there, which you point out is very contemporary, implying that Gandhian perspectives about health were a forerunner to today’s wellness-obsessed culture.

Actually, it isn’t as strange as it seems. The Mahatma himself was introduced to food fads when he studied in London in the 1880s and he kept experimenting with food throughout his life. As I understand, the basic idea was to find a diet that supported good health and cut down on medical expenses incurred on ill health and diseases.

I’m realising that my bad eating habits are my worst enemy, from a health point-of-view, even if I love to sin and eat finger chips and other deep-fried items. When it boils down to what it boils down to, food can either be the best medicine for a healthy life or a slow death.

There is hardly any mention of dessert in this book.

I avoid dessert as much as possible. Early in my career, I would go on travel magazine food trips weighing 85 kg and return home at 101 kg. When one was young, it was okay, but as an elderly gentleman, it is slightly unbecoming if one has to squeeze through restaurant queues just to see others in the line topple like pins in a bowling alley. Hence, I’ve made a conscious decision, however wrong it may seem to you, not to order desserts.

What next?

Right now, I’m working on a sort of history of the world for which I’m being offered something like a million dollars even without having written it. But I am trying my best to live up to it, travelling to obscure places to find out where the world started. And then there are three movies that I’m involved in, all full-out entertainment.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Life Style News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.