Medicalisation is the process of taking non-medical problems and perceiving them as illnesses or health-related disorders. Dr Wolfgang Seidl examines the dangers of this at work in terms of absence, return to work, rehabilitation and organisational and individual wellbeing.

Medical science has advanced impressively and so has the power of the medical profession to make decisions that are not scientific ones.

We forget that medical knowledge is bound up with other forms of knowledge and practice in society, some of them ethical, legal or political. As reflected, for instance, in sick notes or fit notes, return-to-work practices, access to sick pay, disability allowance, and others.

The pandemic has shown yet again where the boundaries are blurred between aspects of physical and mental health, as well as political decisions, inequalities in health and social living conditions.

We have learned to appreciate the mutual influence between medicine and its social context. Or to use another example, doctors have not been trained to ration scarce resources and treatment, yet they are involved in it on a daily basis.

Expansion of the medical into the social

Modern medicine is alleviating and preventing illness but also plays a key role in regulating the conduct of the sick, for example isolation during the pandemic and other infectious diseases or with regard to severe mental illness and suicidal ideation, to name but two obvious examples. Medical knowledge is expanding into more areas of social life, which is known as medicalisation.

By contrast, many people nowadays like to think of themselves as more able to take responsibility for their own health than the rather passive ‘patient model’ suggests. Working with organisations, I often hear wellbeing directors invoke a variation of the so-called ‘psychological contract’ and demand that workplace health is a two-way street where everyone is actively engaged in their health.

Return-to-work or rehab programmes often encounter a fascinating phenomenon when ‘patients’ have medically recovered but the barriers to return to work have become higher rather than lower.

In some of these cases, it’s no longer their health that prevents a return but an unknown conflict with their supervisor or other organisational barriers. When creating a – at that point, new – return-to-work programme years ago, we found that simply putting HR consultancy alongside psychological or medical support drastically increased the successful return-to-work rates. It became obvious that organisational factors play a role.

Some people may appear depressed but they are being bullied or experience a lack trust or purpose; others face neurodiversity challenges that have not been addressed. So, let’s not ‘pathologise’ every human behaviour in the workplace!

This article is not a critique of the successes of medical science, not even the bio-medical model as such, but a call for action not to offload systemic/organisational issues to the medical profession who are stretched as it is.

A lot of stress or misery caused by discrimination, bad management and lack of employee participation in decision-making and co-creation of meaningful jobs has to be addressed as management issue.

Need for a systemic view of wellbeing

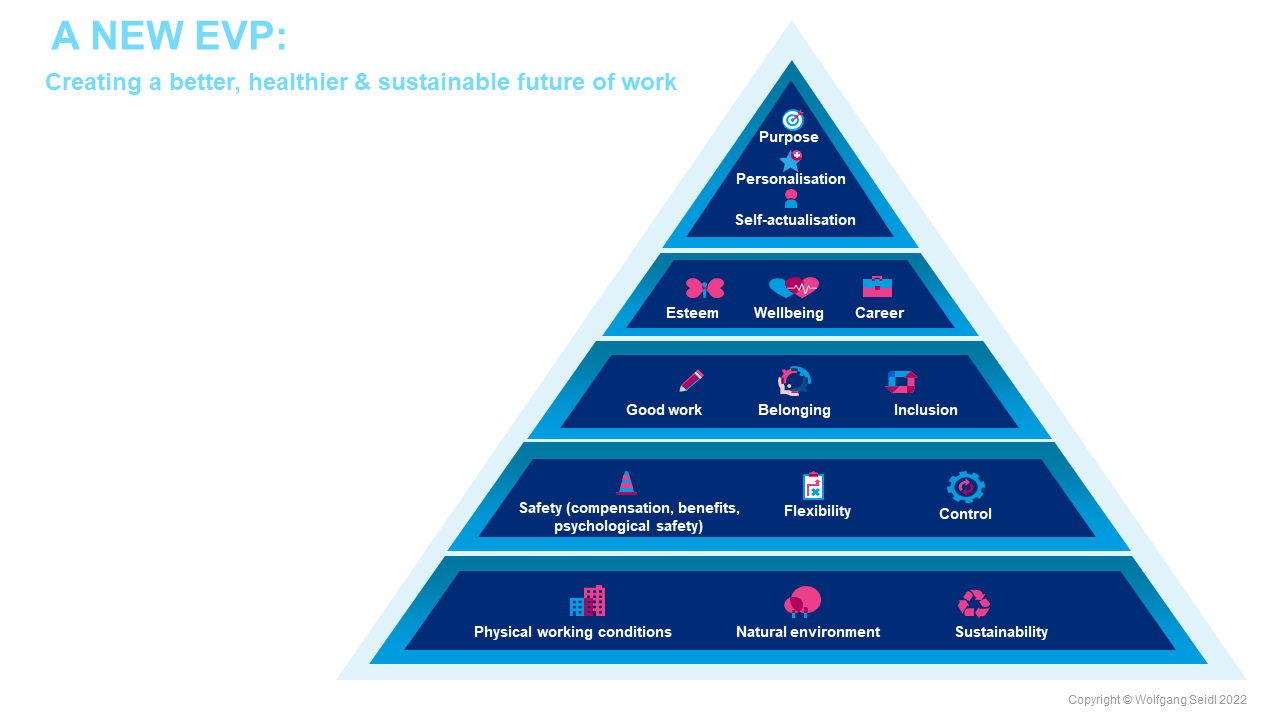

We need to take a systemic view of wellbeing based on the eight-box model below:

In ‘systemic therapy’, a form of psychotherapy, practitioners look at people not only on the individual level, but also as people in relationships, dealing with the interactions of groups and their patterns and dynamics.

While medical science has been crucial in improving health, such as the eradication of smallpox, immunisation against polio and other infectious diseases, environmental changes have often been more influential, for example better housing, working conditions and nutrition.”

It may be helpful to focus not only on an ‘identified patient’ but also on the context and the environmental factors that sustain the identified symptoms.

The appreciation of context and the role of other professionals in dealing with workplace wellbeing will make the medical model more focused and professional not weaker, since definitions, diagnoses and treatments don’t become diluted and almost unrecognisable when applied to every situation.

Take the pandemic as an example; some experts state that we are all suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) now, which renders the diagnostic criteria of PTSD irrelevant.

It also does an injustice to people who have faced critical life-threatening events, such as terrorist attacks, war, rape, prolonged periods of time in intensive care and so on, who benefit from a meaningful diagnosis and empirically-evidenced treatment.

There is no doubt that most other people felt terribly bruised, uneasy and anxious during the pandemic, but that is a different form of pain (and even trauma) that is not the same as PTSD.

While medical science has been crucial in improving health, such as the eradication of smallpox, immunisation against polio and other infectious diseases, environmental changes have often been more influential, for example better housing, working conditions and nutrition. Tuberculosis is perhaps the best-known example in this context.

Another example are smoking-related conditions and the fact that changing the environment by introducing smoking bans in public places had a greater effect on the prevalence of smoking and related lung cancer rates than smoking cessation programmes based on behavioural science.

Taking a big leap forward

We need to be highlighting the role of good management, workplace conflict, social support systems, ‘good work’, psychological safety, and control over one’s own workflow in enhance wellbeing – and avoid medicalised labelling where it’s not needed.

In conclusion, here’s the beginning of what I’d argue is a systemic view of the world of work based on positive psychology, one where our jobs can contribute to our wellbeing and fulfilment:

- The physical environment has become more important than ever, given that organisations want to provide a safe environment that protects people from infections, while at the same time, creating space for social interaction and wellbeing.

- We have also learned during lockdown that connection with nature is hugely beneficial for our physical and particularly mental and emotional wellbeing.

- Environmental and sustainability concerns have moved centre stage and organisations are increasingly aware of their carbon footprint and corporate social responsibility. It is likely that businesses and employees may start appreciating the opportunities in reducing their impact on our environment by introducing flexible working and cutting unnecessary travel.

- Flexible or agile working is inextricably linked to work-life balance and creating work around human needs, such as dependent care responsibilities.

- Health is not just an aspect of physical safety but essentially also linked to psychological safety, where employees are encouraged to bring their whole selves to work without fear of criticism or ridicule. Research clearly shows that teams with high levels of psychological safety are significantly more productive than teams with low levels of psychological safety. Needless to say, medical interventions and occupational health and safety remain essential and at the heart of this model.

- People don’t want to return to the workplace at any cost; but do want to create a ‘good’ return to work and foster a sense of belonging that is underpinned by wellbeing and associated with our purpose in life and specifically at work. Inclusion, diversity and equity are central to success.

- All of the above will have an impact on the whole organisation and ultimately build a culture of health and productivity, as shown in the graphic below:

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Health News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.