Queer cinema continues to be ‘othered’ into a sub-genre, with a sedate growth in mainstream cinema. Funding continues to be the biggest obstacle but not the only one. “Money is tied to things that are controlled by cis-hets who look at filmmaking from a certain perspective,” says filmmaker Onir, pointing out that it is a problem that arises from the notions among those who decide what should be or should not be made.

Flumoxed over funding

Irrespective of being made by cis-gender heterosexual filmmakers (or if it has a cis-het gaze), what the recent string of Hindi films — like Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan, Ek Ladki Ko Dekha…, Badhaai Do, Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui, Cobalt Blue, Maja Ma, etc — proves is that if a producer and/or star back your film, the theme being queer has fewer obstacles going forward.

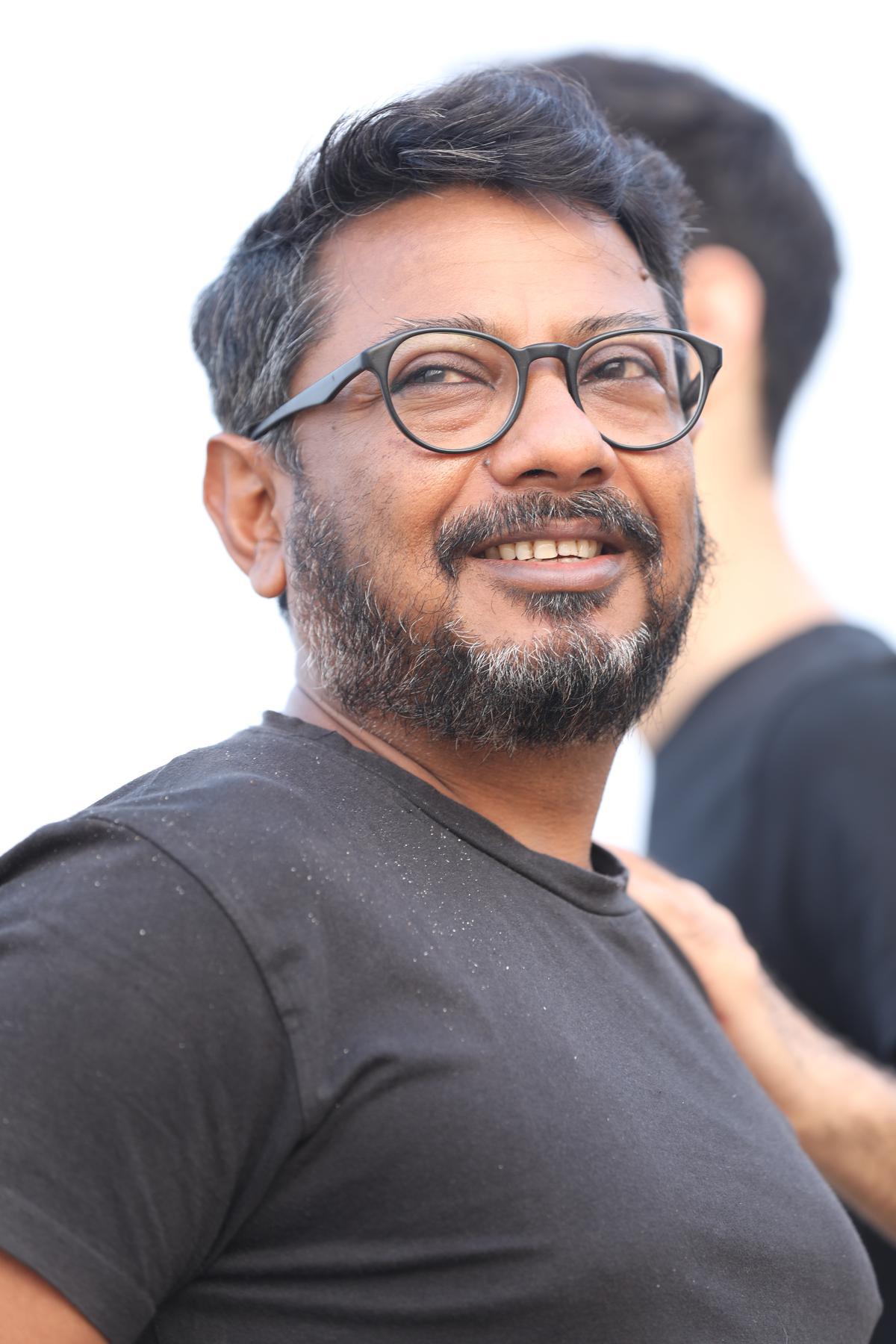

Are these releases a temporary pattern, or the start of something bigger? “A bit of both. Even if it is a trend, the more people venture into this, the more it will be seen as regular,” says Shubh Mangal Zyada… director Hitesh Kewalya, who adds that he got enough support from his producers to make the film.

But one milestone is not enough in a multicultural country like India, he says, and that any attempt, whether profitable or not, helps. “Earlier attempts like Aligarh, I Am, and Fire pushed the door for my film. So every step taken paves the way for the next.”

Hitesh Kewalya

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

What Hitesh says about the support of the producers cannot be undermined. When Prashanth Varma wanted to make Awe,not many were comfortable with its queer theme, he says. “They thought that it was a joke because, in many Telugu films previously, queer ideas were used as jokes,” he says adding that it matters having producers like actor Nani and Prashanti Tipirneni, who prioritise content over earnings.

Unfortunately, there aren’t too many such backers. Some filmmakers, like Roopa Rao (of Gantumootefame), opt for crowd-funding. Roopa made The Other Love Story in 2015 when the concept of a web series was nascent in India. Roopa wanted to go directly to the audience; so she chose YouTube as a platform. “I started to gather funds from friends and family, and as word spread, strangers began pitching in, including a producer from the UK,” she says. There are also exceptional cases, like Shruthi Sharanyam’s B 32 Muthal 44 Vare, which had a trans-man as one of the leads, where the Government helps with funds, something Roopa wishes happens more.

Stills from ‘The Other Love Story’ and ‘B 32 Muthal 44 Vare’

| Photo Credit:

IMDb & Muzik247

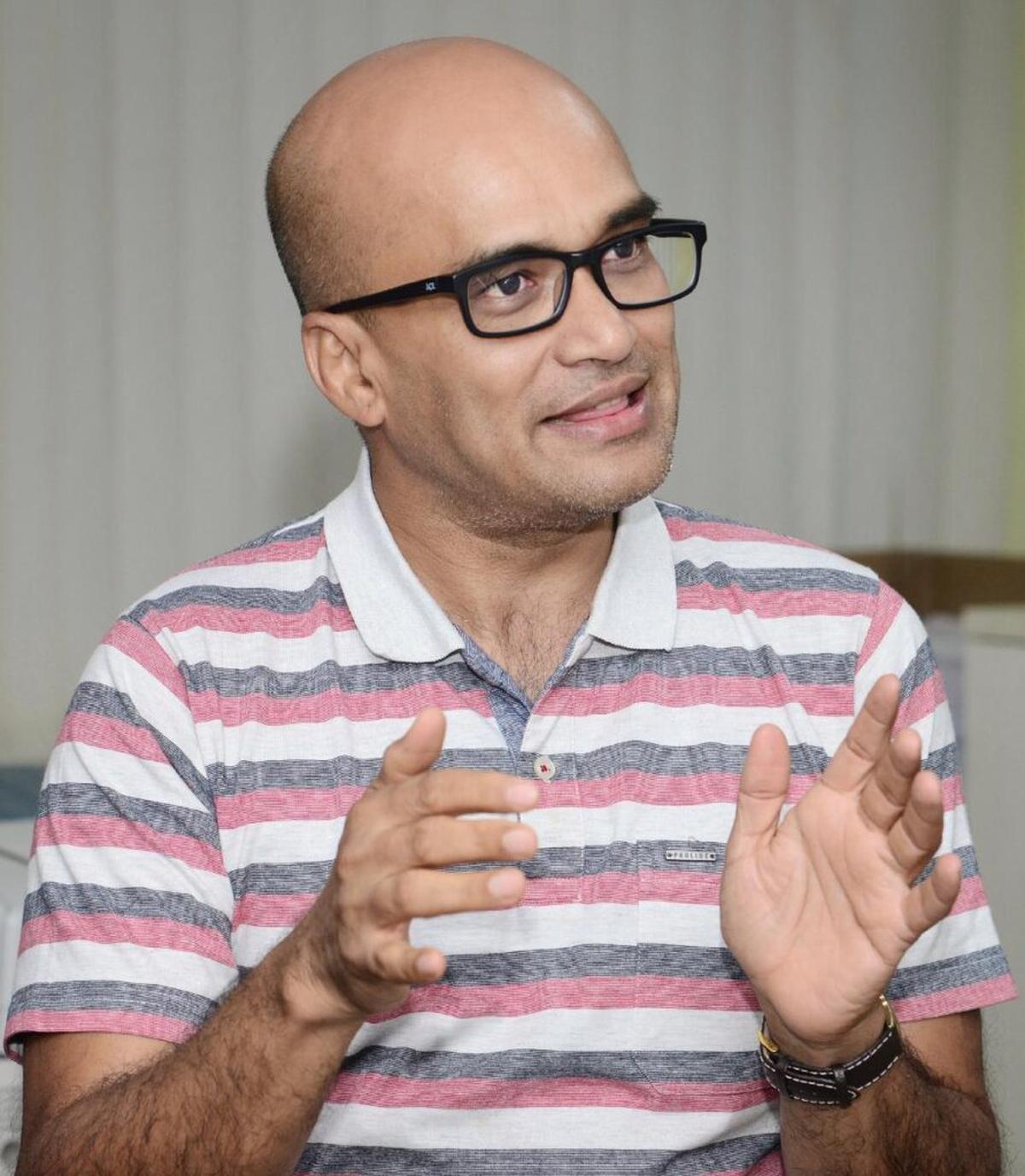

Many queer filmmakers continue to rely on independent sources. Filmmaker Sridhar Rangayan, who has been making films for over 20 years, continues to source his money — he made his first film, Gulabi Aaina, with a budget of two-and-half lakhs and his films now cost over a crore — from independent sources; even his next film Kuch Sapney Apne (a sequel to Evening Shadows) is funded by friends, family, and private investors.

What’s unfortunate is that even if you finally make an indie queer film, Sridhar says, reaching the theatres is difficult. “It’s not easy to recover the amount you invest in marketing. Moreover, multiplexes are dominated by bigger distributors who cater only to star-driven films. Theatres are now trying just to break even, they are not in the mood to support indie films.” Sridhar hopes to see dedicated screens for indie films like in the US.

Sridhar Rangayan

| Photo Credit:

Punit Reddy/Special Arrangement

Even Tamil filmmaker Sudha Kongara, who has made blockbusters with stars, says she does not know how many more mainstream commercial films she has to make, in order to facilitate a project on the lines of her own Thangam (the story of a trans-person from Netflix’sPaava Kadhaigalanthology) to hit theatres. “It’s still a chip on my shoulder that you have to be commercially viable, to do something you actually want later,” she says. “Even the OTT players ask me for commercially-viable content like what I put out in theatres.” She adds that the streamers are also star-driven now.

Nevertheless, Sridhar rests his hope on streaming platforms. “My first queer film, 2003’s Gulabi Aaina, was refused a censor certificate. We had to go through community-based organisations to screen it at film festivals. Only in 2015, when Netflix entered India, did the film get a release on OTT,” he informs.

However, Sridhar and many others say that the space on OTTs is shrinking as well. “Whenever I pitch something, they say, ‘We’re only taking baby steps,’ but their platform already has content that is far more provocative, which people are watching,” says Onir.

Onir

Time for more stars to shine?

So, while it tries to circumvent the star-driven system, should queer cinema also create its own stars? Onir says that it depends on society’s acceptance. “We are living in a country where actors don’t want to come out because of the state of acceptance.”

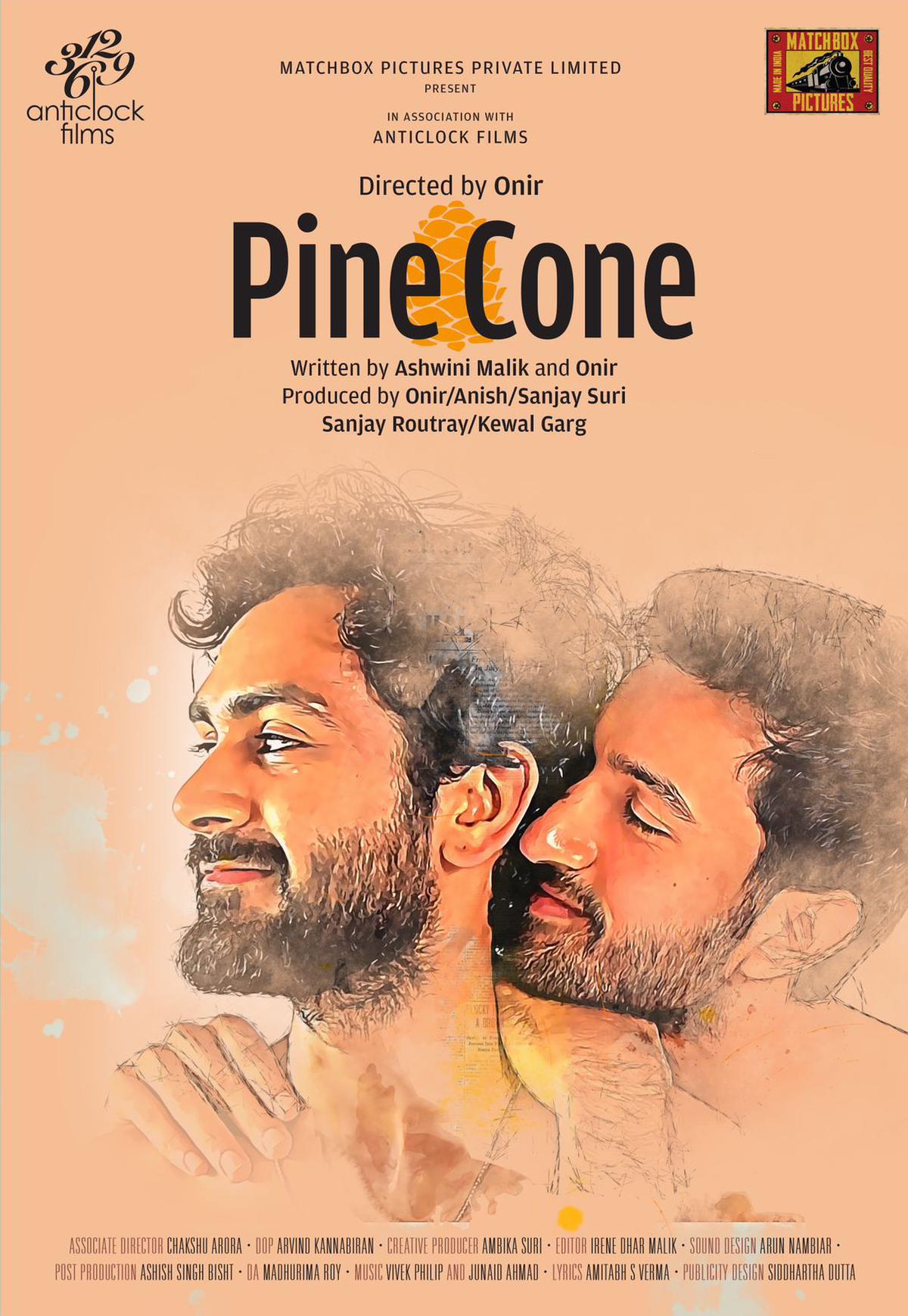

Open-and-out queer actors, filmmakers, and producers are the need for the hour. Adds Onir, “We need more people from the community to talk about their lived-in experiences. That’s why it was important for me to cast a queer actor in Pine Cone.” Onir’s latest is headlined by Vidur Sethi, the first openly gay Bollywood actor.

What does that have to do with queer cinema finding success in the mainstream? A lot.

Queer filmmakers in the mainstream

Poster of ‘Pine Cone’

| Photo Credit:

@IamOnir/Twitter

Firstly, a boost in the mainstream would be counterproductive if most queer content is from cis-het filmmakers who tell queer stories from their perspective. For instance, Sridhar points out how most ‘Bollywood queer films’ are family dramas with just a few queer elements thrown in. “Other elements are narratives structured around these themes, not vice-versa.” Or as queer Kannada author Vasudhendra says, it seems as if most cis-het filmmakers “imagine a cis-man-cis-woman relationship and just swap the gender of one of them,” which fences the real experiences of queer.

It’s akin to cis-men attempting to make the new-age female action star come across as a gender swap with the hyper-masculine male hero, or as Sudha puts it, “semi-pseudo male characters,” and claim that to be progressive characterisation. The presence of queers will ensure the mainstream space is devoid of queerphobic ideas, which are still prevalent in cinema (as recent as this year’s Telugu release Ramabanam)

Vasudhendra

| Photo Credit:

Ramakrishna Sidrapal/Special Arrangement

But Vasudhendra does not believe that queers should only make queer films. “If a story is about a cis-woman who has married a gay man, it’d be better if she tells the story from her point of view.” But only when queers start telling their stories will others learn their perspective and try to do better, he adds. “It’s like how the earlier Dalit stories, that were written by non-Dalits, were mostly sympathy showers with no nuances of the life of Dalits. That changed. So did stories of women. So should be the case with queer stories.”

Sudha understands this. The filmmaker met trans people and took six months to prepare for her short in Paava Kadhaigal. “But I will never know if I am doing justice to it. I am someone who will have qualms with that.”

Some producers see queer cinema as mere tokenism. “Many a time, they are like, ‘Hey, we have done one queer film, and we’re done.’ Are our lives so plain and homogeneous that you make one story and it’s done? They don’t tell a straight director, ‘We’ve already done 10 straight stories,’ right?” questions Onir.

Sudha Kongara

| Photo Credit:

Pichumani K/The Hindu

Tokenism in queer cinema

There is an idea that’s floating around on how queerness can reach the mainstream; similar to having cis-gender men and women play supporting characters, can’t we have queer characters as well in movies led by cis-genders? Would that not help in normalising queerness in a cis-heteronormative space?

Filmmakers caution that such writing could amount to tokenism if not given its due respect and dignity. Onir wonders if this means that the queer character’s queerness is to be watered down. “Have you ever heard someone say that this person is not wearing his straightness on his sleeve? Why does my life have to be subtle? So, a queer character should be treated with as much dignity as you treat other characters,” he says.

It is also important that queer characters do not seek validation from cis-het society. “Everything about us is not about them; we are leading our lives as well.” And he also points out that such attempts be not put as ‘having queers in films that do not speak about queer issues’. “I hate the word ‘issue’. What ‘queer issue’ do films like Call Me By Your Name or the French film Close talk about? Not all heterosexual stories are about ‘issues’. Why is my life an ‘issue’?”

A still from ‘Close’

| Photo Credit:

Prime Video

Acceptance in society

All this talk ultimately rests on the audience of a film and how society accepts queers. On that front, many seem pragmatically optimistic. “Ten years ago, if I went to a public institution and asked them if I can speak about queerness, they’d reject the idea without a second thought. But now, many colleges are requesting me to come and speak about it. Society is gradually opening up,” says Vasudhendra.

Cinema and pop culture play a vital role in this, and it is up to the collective society to ensure that there are more avenues for queer stories, more space for queer discourse and more queers telling their stories.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.