In September 2020, President Xi Jinping conferred medals on the heroes of China’s battle with coronavirus and declared that its handling of the pandemic had, once again, proved the superiority of Beijing’s political system.

A little over two years later and, far from beating the pandemic, China is suffering record cases and lockdowns, its Covid-19 policy is confused and it has no clear exit path given the country’s low vaccination rates among the elderly and its healthcare vulnerabilities.

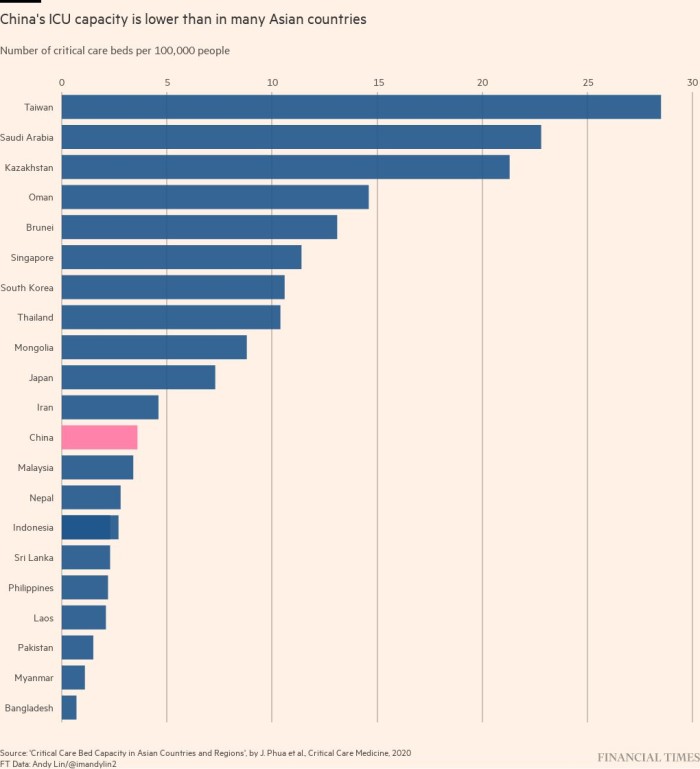

With the economic and social costs mounting from conflicting policy directives, Beijing needs to set explicit criteria for reopening based on vaccination coverage and the availability of intensive care units for treating an inevitable exit wave of cases, according to Yu Jie, a senior research fellow at Chatham House, a UK think-tank.

Ultimately, such conditions must be set, she said, “because it is no longer just a public health question, it is an economic question”.

Coronavirus vaccinations are one of Xi’s core challenges. According to the latest official data, a third of China’s 267mn people older than 60 have not received their third vaccine dose. The booster is required to attain high levels of protection against the Omicron variant.

A big problem lies in Chinese culture, which is more risk-averse than many other countries when it comes to diseases and vaccines, said Xinran Andy Chen, an analyst at China consultancy Trivium.

While a relatively high vaccine hesitancy rate among China’s elderly population predates the pandemic, the problem has been exacerbated by official messaging about the dangers of Covid over the past two-and-a-half years.

Despite the Communist party’s enormous powers of social control, ordering the elderly to vaccinate is viewed as a step too far, even for Xi, because of fears it would spark “dramatic social resistance”.

“They don’t want to force through a vaccine mandate [but] they can’t afford old people dying. So that is why stringent Covid controls are still in place,” Chen said.

This month, Xi attempted to soften zero-Covid restrictions. The State Council, China’s cabinet, reduced quarantine periods and stopped tracing of second-degree close contacts of confirmed positive cases. The moves were also aimed at easing pressure on the centralised quarantine system that is now housing more than 1mn people.

However, Ernan Cui, an analyst at Beijing research group Gavekal, said the attempt to stabilise the economy had only created “widespread policy uncertainty” and made “the pandemic even harder to control”.

A Beijing-based government adviser close to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention said the timing of “opening up” hinged on producing higher quality vaccines and making them widely available.

He pointed to more than a dozen new vaccines, including six using mRNA technology, under development. Beijing, however, cannot tolerate a death rate of 0.2 per cent for cases as seen in Taiwan and officials will not rule out a return to Shanghai-style citywide lockdowns if outbreaks are deemed out of control.

“There is no way we can open up right now,” he said.

Experts believe that the main Chinese-made vaccines provide high levels of protection from severe illness and death with three doses. But they are less effective and fade faster than the mRNA technology developed by BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna, which are used across the west. The Chinese are also untested in the event of a huge outbreak.

Chen, of Trivium, added that the Chinese government believed the benefits of foreign-made vaccines were outweighed by the political and economic risks.

From Beijing’s point of view, “the cost of losing national pride, the cost of losing market share to a foreign competitor, is much greater than using a marginally better vaccine that is not 100 per cent effective in preventing infection”, he said.

This is despite the enormous economic pain. China’s growth has slowed to its lowest rates in decades while youth unemployment has risen to a record 20 per cent as relentless lockdowns sap consumer demand and hobble manufacturing.

As case numbers soar, there are increasing signs of central intervention in cities across China, meaning a return to mass testing and quarantine.

In one example, following an inspection this week of the south-western megacity of Chongqing, vice-premier Sun Chunlan, who is Xi’s top zero-Covid enforcer, ordered officials to eliminate all community transmission in eight days.

That target, a local official said, was “impossible” to meet, meaning the situation risked mirroring events in Shanghai this spring when an initial two-day lockdown persisted for two months.

Another challenge to China changing course on zero-Covid would be the government narrative. Authorities need a different message to convince a fearful public that it is possible to live with the virus.

Hu Xijin, a former editor of the Global Times, a nationalist newspaper, told the Financial Times that ordinary Chinese people were “very worried” about the risks of infection, especially the dangers to children and the elderly, as well as the threat of quarantine.

Hu, who is in quarantine himself, said state media had not intentionally run campaigns to emphasise the dangers of the virus. “I never received such instructions during my final two years as the editor-in-chief,” he said.

However, he said that after watching the handling of the pandemic in the US and much of the west — and the high death toll — many Chinese gained a strong “sense of pride” in the country’s zero-Covid response.

Liqian Ren, who manages China investments at US-based WisdomTree Asset Management, believes abandoning zero-Covid must be preceded by a stark shift in domestic messaging from the very top: Xi himself.

“The propaganda machine needs to change, to say ‘this is not a scary disease’, to say ‘we have hospitals’ and ‘this is the success of the party’,” she said.

Underscoring the shortcomings of China’s healthcare system, the Asian Development Bank last month approved a $300mn loan to improve public health services in two of China’s poorer regions. Its experts noted that the pandemic had highlighted “gaps” in the state-funded health system and shown that China’s hospitals were “particularly vulnerable to admission surges”.

Ben Cowling, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Hong Kong, said China’s healthcare system risked being overwhelmed like that of Hong Kong earlier this year if it did not follow the likes of Singapore in preparing for an exit. That would involve radically changing the zero-Covid rules so that only severe cases were hospitalised.

“In Hong Kong, there was no concrete plan for exit; even in early March of 2022 [at the height of a big outbreak], there was still isolation of very mild cases in hospital and in isolation facilities when the resources should have been saved for the more severe ones,” he said. “The preparation makes a big difference.”

Others are less pessimistic. Ryan Manuel, managing director of Bilby, a consultancy that analyses Chinese government documents, said Beijing had signalled that it would ultimately embark on a staged reopening based on the ability to parachute in medical support teams from around the nation.

While this meant that any reopening would be “piecemeal”, it also meant “there won’t be a wholesale ‘let it rip’”, Manuel said.

Additional reporting by Maiqi Ding in Beijing and Eleanor Olcott in Hong Kong

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.