A small orchard on the banks of the Elbe River in northern Germany, overgrown and circled by seagulls, holds the key to the country’s Russia-free energy future.

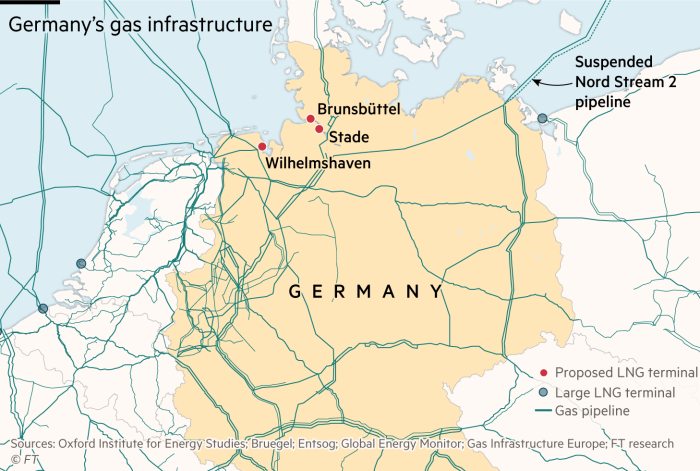

The orchard, close to the city of Stade, will soon be cleared to make way for a €1bn liquefied natural gas terminal, one of three planned that should help Germany cut its dependence on Russian gas.

“The location is perfect,” said Jörg Schmitz, senior LNG project director at chemicals group Dow Germany, gesturing to the wide sweep of the Elbe, the North Sea to the west and the port of Hamburg, Germany’s largest, to the east.

If Schmitz’s vision is realised, Stade will become a hub in the global trade of LNG, gas that has been supercooled to minus 160C so it can be shipped around the world on tankers. “If it all goes to plan we’ll see about 100 landings a year here, up to Q-Max size,” he said, referring to the world’s biggest LNG carriers, each longer than three football pitches.

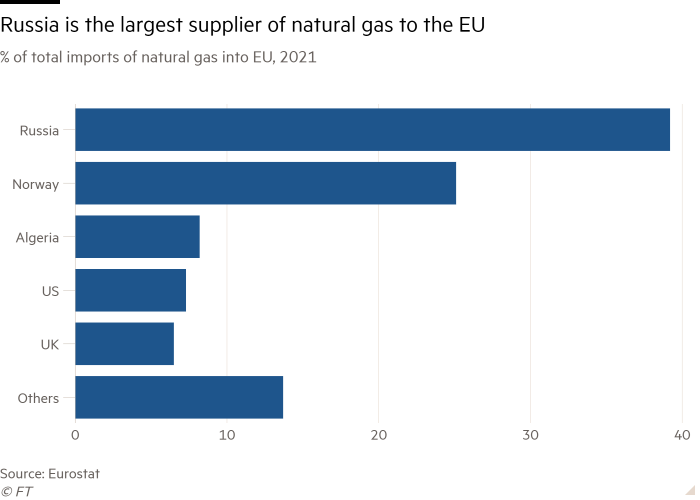

Stade is at the forefront of a revolution in German energy. Just days after Russian troops streamed into Ukraine, chancellor Olaf Scholz announced plans to radically reduce Germany’s reliance on Russian energy. LNG will be vital to the plan to reduce Russian natural gas imports from 55 per cent of the total to 10 per cent by the summer of 2024.

But the switch will be a challenge. Germany’s new dash for gas could clash with its commitment to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2045. It might also struggle to source all the LNG it needs.

“The million dollar question is whether they’ll be able to find enough LNG,” said Frank Harris, an expert on the fuel at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “There’s relatively little new supply over the next two-three years.”

The policy shift is being implemented with a speed that is unusual for Germany. In the weeks after Scholz’s speech in late February, the government rushed to charter four specialised ships known as floating storage and regasification units, or FSRUs — tankers with heat exchangers that use seawater to turn LNG back into gas.

The first FSRU comes online in Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea this year. They will operate as a stop-gap until the permanent terminals come into operation. So far three potential sites have been identified for those — in Stade, nearby Brunsbüttel, also on the Elbe, and Wilhelmshaven.

Dow has been working on building a gas terminal in the area for the past five years. “The idea was you should diversify your gas supply and not allow yourself to become too dependent on one source,” said Schmitz.

Chartering the four FSRUs so quickly was a coup for Germany — there are extremely few suitable vessels available. But finding the ships was only half the battle. “The big challenge is to fill this capacity with LNG, and that will be difficult because the resources on the market are so scarce,” said Andreas Gemballa, director of LNG at Uniper, the German energy company.

Ironically, the largest source of new supply expected in the next two-three years is from Russia — the Arctic LNG-2 project on the Gydan Peninsula in northern Siberia. But that’s looking “very challenged now”, said Harris, largely because sanctions have restricted Russia’s access to financing and technology, while some western buyers might not buy gas from the project.

Qatar could prove to be a big source of LNG for Germany, and its production of the fuel is due to increase 60 per cent by the middle of the decade. But 90-95 per cent of its current output has already been sold on long-term contracts.

That reflects another problem for Berlin — LNG contracts are typically long-term. But having pledged to make Germany carbon-neutral by 2045 the government might be reluctant to commit to importing fossil fuels for 20 years or more.

“Germany is saying — we want all this LNG, but we also want to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, including gas,” Harris said. “It’s a mixed message.”

In addition, a lot of the LNG Berlin has its eye on is indexed to the price of oil or, if coming from the US, to Henry Hub, the US gas benchmark, which can sometimes be higher than Dutch TTF, the European marker. That exposes buyers to risks of financial losses. Such contracts “don’t conform to the way we price gas in Europe”, Gemballa said.

For that reason, big LNG producers such as Qatar might prefer to strike deals with Asian countries that have fewer qualms about signing 20-year contracts and are more comfortable with oil-indexed prices, Harris said.

Robert Habeck, the Green economy minister, personifies Germany’s dilemma. He has travelled to Qatar and the UAE to discuss energy co-operation and overseeing the start of construction of the first floating LNG terminal in Wilhelmshaven in early May.

But he has also warned of the dangers of Germany getting stuck with expensive infrastructure that could lock in its dependence on fossil fuels.

“In the short term we’ve been pretty successful at replacing Russian gas, but we have to make sure we’re not too successful,” he said late last month. “We don’t want to spend the next 30-40 years building up a global natural gas industry that we don’t really want any more.”

The trick is, he said, to build “three or four times as many kilowatt hours of renewable energy” as the natural gas resources now being developed to quench Germany’s short-term thirst for the fuel.

Timm Kehler, managing director of trade body Zukunft Gas, does not see the imminent wave of gas infrastructure construction as a problem: the new terminals will also be designed to handle “green hydrogen”, a low- or zero-carbon fuel. “[They] will be a bridge into a future where we don’t import gas in the form of LNG but hydrogen in the form of ammonia,” he said.

For Dow’s Schmitz, Berlin’s sudden enthusiasm for LNG is a vindication. “The plan [for a terminal] always made commercial sense,” he said. “But now it has geopolitical significance, too.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.