Jitish Kallat’s ‘Epicycles’ at Chemould Prescott Road.

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

Weaving one’s way through a Jitish Kallat exhibition affords a staggering range of visuals: a mechanical engineering workshop replete with lathe machines and high-speed steel tools, wide canvases with in-line drawings reminiscent of a master of architecture studies, images collapsing into each other to form a numinous whole, and mathematical equations twisting into linear sculptures.

In the past, the Mumbai-based contemporary artist has exaggerated sliced apples to show glowing star fields, and physically exposed his artworks to wind and fire, marrying botanical elements such as shells and molecules with socio-political commentary. One could argue that Kallat overwhelms your senses, that there is too much happening on the canvas for one to ever harmonise it. But he is not the enfant terrible of the art world and does not aim to be one either.

Artist Jitish Kallat.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

“The medium follows the impulse, as artworks typically arrive as intuitions bearing within them a discreet ‘birthing manual’ for their arrival in the world,” he says. “The complex part of the artistic process is identifying and unearthing that manual of instructions and an external stimulus that often unravels an inner monologue, which in time might materialise as a piece of work.”

Blending space, time and realities

His latest outing, Otherwhile, is an accumulation of stillness, of static imagery with a quirky treatment. It is also an assembly of various ideas that have stayed consistent through his work, which situates itself at the intersections of science, philosophy, history, mathematics and natural geometry. In previous exhibitions, Kallat created gesso panels with black epoxy pigment and transparent lacquer. In Otherwhile, his preoccupations are more wide-ranging, not necessarily held down by the constraints of a form but reaching out to more abstract realities.

‘Elicitation (Cassiopeia A)’ at Chemould Prescott Road.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

An example of diverse references and intuitions coming together is ‘Epicycles’, where markers of change documented in his studio are woven together with photographs drawn from the historic 1955 MoMA exhibition, The Family of Man — which brought together hundreds of images from photographers around the world in the decade following World War II. “Coalescing the immediate studio images with a glimpse of humanity from a distant time and place yields a composite portrait of time and transience,” he says.

Of abstractions and triangulations

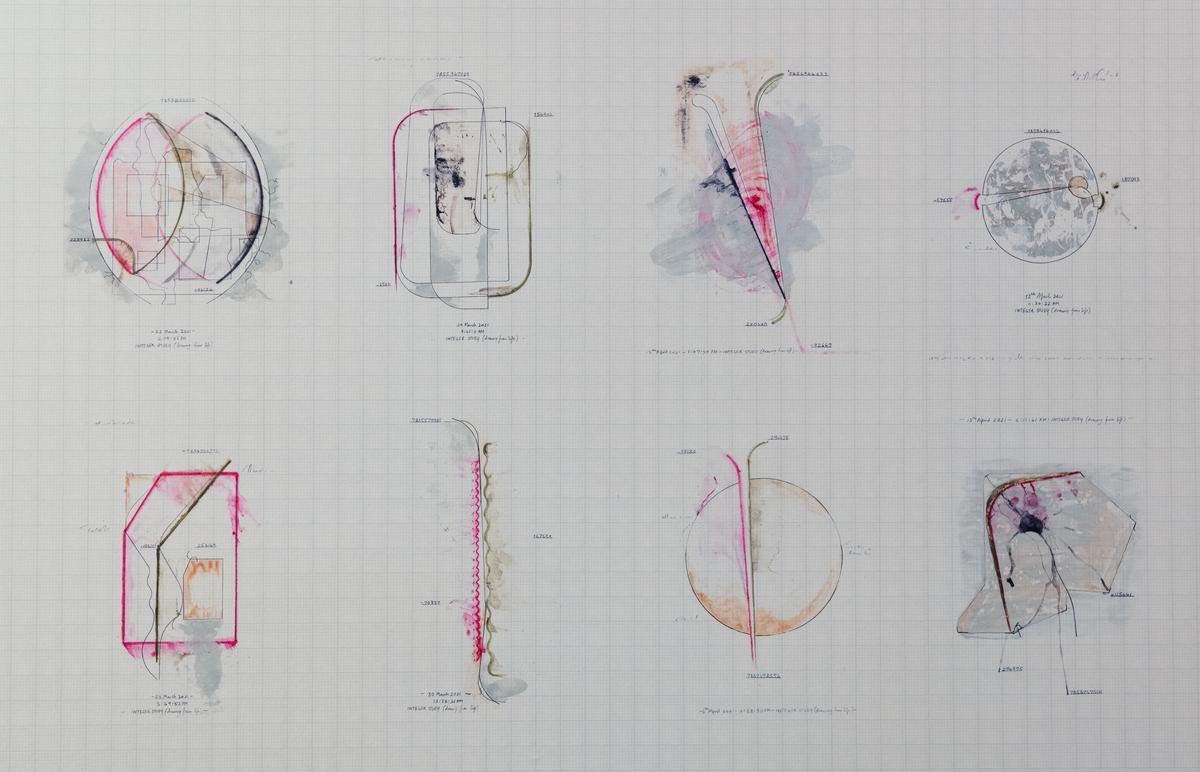

In Otherwhile, Kallat continues to juxtapose contrasting worlds, both alien and galactic, to make sense of the magic and even abstractions inherent in any life form. ‘Elicitation (Cassiopeia A)’ is a three-dimensional visualisation, produced from NASA’s open-source files, of a dead star’s remains from a stellar explosion that occurred 11,000 light-years away. Moving away from the cyberpunk portrayals of all things space, this white, jagged sculpture — that resembles stalagmites in a cave — is placed on a stack of Bienfang gridded paper, the drawing surface for Kallat’s year-long project ‘Integer Studies (drawing from life)’. The latter, a wallpapered ledger of forms and numbers started in 2021, explores “the planetary present through a daily count of the world population — 365 drawings that each display the algorithmically estimated births and deaths that have occurred up until a specific time each day”.

Kallat’s year-long project ‘Integer Studies (drawing from life)’.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The algebra of it all is not a mere coincidence. It has informed his work since his first exhibition at Chemould in 1997. He acknowledges that “numbers, dates and at some level fundamental geometry” have been of interest to him. The source? The overarching logic that can explain events across time and space. ‘Epilogue’, for instance, was a recital of every moon that his father saw in his lifetime. “In ‘Integer Studies’, our planetary presence is reflected upon through the abstraction of numbers,” he says. “In these works, painterly abstraction contrasts with precise data, forming a triangulation of life by mapping birth, death and time.”

Kallat brings Gandhi to Kochi

The artist had curated the 2014 edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale to wide acclaim. This year, he returns on a smaller scale, presenting Tangled Hierarchy, a “speculative curatorial thought experiment with historical handwritten notes by Mahatma Gandhi at its centre” — communications with Lord Mountbatten on the imminent partition after Gandhi had undertaken a vow of silence to protest the action.

The exhibition first opened on June 2, 2022, at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton in the UK, exactly 75 years after Gandhi wrote those words. Artworks, archival documents and objects entangle into an interwoven system of inquiries. “The weeks and months of this exhibition run alongside the tumultuous months of partition 75 years ago,” Kallat says. “So, exhibiting it in the South of India [brought down by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art] has a different resonance since the pain of partition was experienced here with some geographical distance.”

Has Indian art been successful in working along the margins of this triangulation that Kallat describes? Have artists confronted the realities of our time in styles and forms uniquely their own? Or, simpler still, how far have we come? “It’s 25 years [since my first exhibition], so a lot has changed as we now host large art events like the Kochi Biennale and our neighbouring countries have also become hosts to interesting events and exhibitions. Earlier artists from South Asia were always guests in other countries,” he says. “But that said we do have a long way to go in terms of institutional development [in terms of museum infrastructure] and art education [the ambivalent role of the state in supporting the arts].”

Otherwhile is at the Chemould Prescott Road in Mumbai till January 4, 2023.

The writer is an author and editor based in Mumbai.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Entertainment News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.