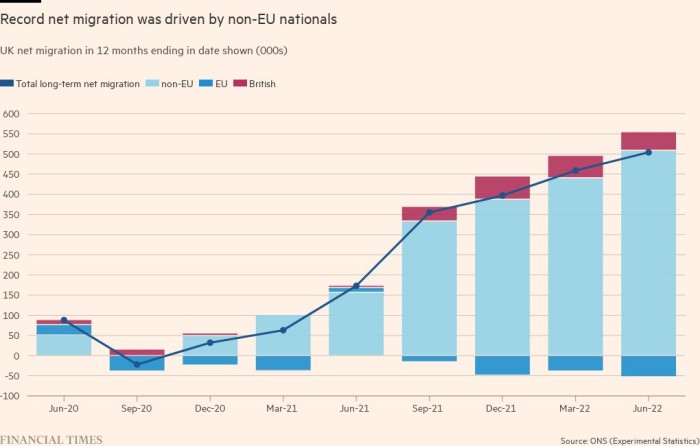

The record high of 504,000 in UK net migration shown in data this week looks at odds with business leaders’ claims that post-Brexit visa rules are choking off growth in the economy.

Politicians have been giving equally mixed messages. Prime minister Rishi Sunak this week promised to cut overall immigration, while assuring the CBI that he would “unapologetically create one of the world’s most attractive visa regimes for entrepreneurs and highly skilled people”.

Meanwhile, Labour’s Sir Keir Starmer, the opposition leader, said he would be “pragmatic on the basic lack of people”, but that any loosening of visa rules would come with new conditions for business to “help the British economy off its immigration dependency”.

In reality, employers have not been the main driver of the latest surge in immigration — nor would loosening the rules solve all their problems.

What was behind the surge in migrants?

Students were the biggest group driving the surge in immigration from outside the EU, according to Office for National Statistics data for the 12 months to June. This could be partly a post-pandemic effect, as people who began courses remotely switch to in-person learning; a new visa route for students at top universities to work after graduating could also have acted as a draw.

But international students are unlikely to drive long-term population growth — even if universities escape a clampdown on visas ministers are reportedly considering. Most leave the UK after graduation, so a spike in arrivals is likely to mean higher emigration in a few years’ time.

Humanitarian routes for Afghans, Ukrainians and Hong Kong residents were the next most important factor behind the surge. Many of these people have now moved into work. But an ONS survey of Ukrainians found professionals were often in low-paid jobs in hospitality and the food sector, because their English was not yet good enough or their qualifications not valid.

Overseas hiring played a much smaller part, with work visas for non-EU citizens rising by 59,000 in the year to June. The latest Home Office figures on visa issuance confirm that this increase was chiefly due to a surge in recruitment of doctors, nurses and care workers, with smaller numbers coming into the tech sector, financial services and other professional roles.

Why do employers want the visa system to change?

The post-Brexit “skilled worker” visa regime is relatively liberal for highly-paid graduate jobs, although smaller employers often find it difficult to meet the one-off cost of a licence to sponsor migrants.

But businesses cannot hire migrants to fill lower-skilled roles in many of the areas where vacancy rates have been highest — to work as baggage handlers, for example, or in sectors such as hospitality or logistics that previously relied heavily on workers from the EU. The ONS data showed more EU citizens left the UK than arrived in the year to June.

Business groups say the requirement for jobs to meet a certain skill level — roughly equivalent to A-levels — is more often an obstacle than the salary threshold of £25,600, with HGV driving one of the most prominent examples of occupations that are not eligible for visas as a result.

But they are also pressing the government to speed up a long-promised review of the Home Office’s shortage occupation list, which sets out the roles that can be filled by migrants paid below the job’s usual going rate.

Charles Goodhart, an economist and former Bank of England official, argued at a conference this week that the visa system did not match the needs of the economy. “I think the British government is actually on the wrong track, because the proportion of those going to university in our population has increased dramatically,” he said. “What we need is not the skilled people — we have got plenty of skilled people — what we need are people to do the jobs that the population does not want to do.”

Can labour shortages be solved by immigration?

Goodhart’s view is not popular with ministers, who are understandably reluctant to let businesses hire migrants instead of offering pay and working conditions that British workers are prepared to accept.

But the CBI business group argues that labour shortages — partly due to the post-Covid rise in economic inactivity — are now so severe that they are stopping employers making the investments in skills and technology needed to shift the economy to a higher pay and productivity model.

“We don’t have enough Brits to go round,” Tony Danker, CBI director-general, said this week, calling for fixed-term visas in areas where “we aren’t going to get the people and skills at home any time soon”.

But economists warn that migration should not be seen as an answer to a shrinking workforce.

Alan Manning, a former head of the government’s Migration Advisory Committee, said visa schemes could be used to solve specific labour issues — when politicians think a shortage is serious, and there is no quick way to train local workers or make the jobs more attractive.

But when migrants spend their earnings, they raise demand for labour as well as supply, Manning noted — so to see migration as “a solution to a generalised labour shortage” is a “fallacy”.

Additional reporting by Daria Mosolova

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.