Picture New Years’ Eve 2015. As you wait for the countdown to midnight, you hear the following predictions for the coming months and years …

The UK will vote to leave the European Union, causing economic chaos and resulting in a game of musical chairs with five prime ministers in the next seven years.

The US will elect a reality TV star as president; Donald Trump will spend most of his time in office playing golf and upending the economic relationship with China.

In China, President Xi Jinping will abolish term limits and tighten his grip on politics, society and economic activity.

Across the globe a pandemic will break out, resulting in millions of deaths and disruption to the daily lives of billions. Even as the outbreak fades, offices will remain half empty as large numbers of people work remotely. China, where the virus initially emerged, will be the last country to exit lockdowns.

Markets will initially crash, then go on a tear with the most speculative investments you can imagine exploding in value before crashing.

Russia will invade Ukraine, but its smaller neighbour will fight back bravely against all expectations. Despite claims of neutrality by the South African government, the US ambassador accuses it of selling arms to Russia.

Read: Rand rattled: New record low after US claims of SA-Russia arms

Stage 6 load shedding will become a regular feature for South Africa as an Eskom CEO survives an assassination attempt. It will also transpire that a billionaire president keeps large amounts of cash in a couch on his game farm.

Would you have believed any of this?

Highly unlikely. The point is the future is very unpredictable and even unimaginable. Fact can be stranger than fiction. Echoing former US secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld’s known and unknown knowns and unknowns, there are also bouts of unpredictability.

There are events that we know precisely when they will occur, such as an election or a World Cup final, but we don’t know the outcome. There are events that we know will happen at some point in the future, like the next hurricane to hit the southern US, but we don’t know when or where, or how things will turn out.

There are events that are considered possible but unlikely, such that when they do occur, we are surprised and the few Cassandras that warned against them look like geniuses. The Russian invasion falls into this category.

But also remember that for each such genius there are many doomsday predictions that never happen – and this is particularly true for market crashes.

There are events considered high probability that never occur. Some things are the result of complex processes that are difficult to predict at each step. The recent global inflation surge falls into this category.

Read:

Some things are predictable but take longer or less time than expected to materialise. And then there are things that come completely out of the blue, such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the 9/11 attacks.

All of this applies directly to investing. Financial markets are very efficient in pricing in the known but struggle with uncertainty. As new information comes in, markets quickly discount it.

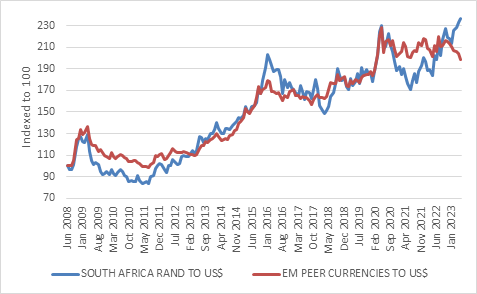

For instance, since late last year as it became clear that load shedding would be both more severe and last longer than previously expected, the rand has increasingly decoupled from its peer currencies as the chart below shows.

Read:

While other emerging market currencies have gained against the dollar this year, the rand has steadily lost ground.

To Russia with love?

However, the news about the alleged arms sales was a shock (and is shocking).

Big surprises like these lead to big market moves, both up and down.

Nenegate in 2015 was another example. The rand had been on a weakening trend for some time, but the shock axing of then finance minister Nhlanhla Nene, perceived to be a bulwark against corruption and fiscal profligacy, saw the rand lose 4% on the day and another 5% the following day.

Rand and other emerging markets commodity producers against the dollar

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

What the chart also shows, however, is that such divergence tends not to last and that similar blowout episodes (2001, 2008, 2015, 2020) were reversed.

This episode is unlikely to be any different, so be careful of a knee-jerk reaction.

We don’t know when, of course, but the rand is very likely to recoup some of these losses in the future.

For that to happen, we’d probably need to see some better news on load shedding and some repair in the US/SA diplomatic relationship. The risk of sanctions being applied on South Africa is very low, but the bigger danger is losing preferential access for exporting into the US under the African Growth and Opportunities Act (Agoa) when it is up for renewal in 2025.

South Africa exported some $3 billion under Agoa last year according to JP Morgan, about a fifth of total exports into the US. To state the obvious, South Africa’s current exports to Russia do not remotely match this, nor can any reasonable expectation of future trade.

Read:

The ANC ditches South Africa for Russia

Fears Russia row will hit SA-US trade ties

Bank bosses and their national conversation responsibilities

Most importantly, a rand recovery requires a retreat in the US dollar. This in turn will require that the US Federal Reserve stop hiking rates. Last week’s US inflation data supports the view that they will, but also suggests that rate cuts are still some way away.

A hawkish change to expected European Central Bank (ECB) rate hikes currently priced into markets could also result in further US dollar weakness. Always remember that an exchange rate is not a price but the swap ratio between two currencies and two sets of considerations always needs to be considered.

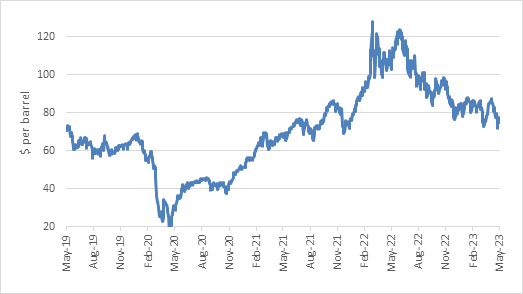

Meanwhile, the weaker rand will put some further upward pressure on domestic inflation; fortunately the dollar oil price has also been under pressure.

The extent to which rand weakness results in higher inflation depends on how businesses pass on higher import prices.

This in turn depends on whether these businesses feel domestic consumers can absorb higher the costs. Nonetheless, it suggests that the South African Reserve Bank will raise rates later this month. Unfortunately, this will further weaken the economy, much as load shedding does.

Brent crude oil price, $/barrel

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

While a currency slump generates attention and causes great anxiety, it is not all bad.

South Africans have considerable global investments, and these increase in value all else being equal.

For instance, over the past year, global equities are up 7% in dollars and 23% in rand terms.

Unfortunately, not all South Africans have offshore investments, but those who do are probably not poorer on balance.

Exporters also benefit greatly from being able to repatriate their earnings at a more favourable exchange rate. And local businesses that compete with imports are advantaged, provided they don’t rely too much on other imports for inputs. The rand therefore acts as a shock absorber for the overall economy, rebalancing activity and income in times of stress.

Dancing on the ceiling

South Africa is not the only country with political intrigue causing financial market uncertainty.

The most pressing current example is the fight over raising the US debt ceiling. It is a limit imposed by the US Congress on the total outstanding amount of debt of the Federal Government. It currently stands at $31.4 trillion, and as the famous debt clock in Times Square in Manhattan will tell you, it has already been reached.

The US Treasury now relies on temporary “extraordinary measures” to pay all its bills, but once these have been exhausted, it can only pay out what comes in through tax revenues. It cannot legally issue any more debt or roll over maturing bonds. Tax revenues are substantially less than expenditure – in other words, the US runs a large budget deficit – but tax revenues are also lumpy while spending is constant.

Therefore, unless the debt ceiling is lifted, the US will skip paying some of its bills, with the biggest concern being that it might miss interest or capital payments on bonds, constituting a default.

Why is there a debt ceiling in the first place? Prior to its introduction in 1917, Congress, which authorises spending in the US, also had to approve individual bond issues. But the massive financing needs of the war meant this was impractical and the debt ceiling was introduced to give the treasury leeway to borrow money as needed.

In other words, it was meant to facilitate efficient borrowing, not constrain it – and for several decades, it was routinely raised as the economy grew and borrowing requirements changed. But in recent years it became a political football, especially when one party controls Congress and another the White House.

Read: Why America has a debt ceiling

The current moment is particularly uncertain not just because of divisions between the Republicans who control the House and Democrats who control the Senate and White House, but also because of divisions between Republicans. The Republican Speaker in the House has only a loose grip on his caucus, and some of its members seem perfectly happy with the idea of defaulting unless the Democrats agree to big spending cuts (although they were perfectly happy to raise the debt ceiling when Donald Trump was in office).

Trump, still the front-runner to be the Republican nominee for president next year, encouraged a default in an interview last week. This adds further fuel to the fire.

Now what?

The most likely outcome is still a last-minute deal to lift the debt ceiling, or at least to do so temporarily.

The Winston Churchill quote that the “United States can always be relied upon to do the right thing – having first exhausted all possible alternatives” is often used in this context, and hopefully applies (his mother was American, by the way).

But the risk of this not happening is larger than previous such episodes. While there is great uncertainty whether the debt ceiling will be lifted, there is even greater uncertainty as to what will happen if it doesn’t.

Firstly, there is a chance that President Joe Biden will simply ignore it, forcing a constitutional showdown. The 14th Amendment in the US Constitution stipulates that “the validity of the public debt” issued by the US government “shall not be questioned”.

The alternative is to prioritise interest payments ahead of paying salaries and pensions to avoid a debt default. This will be a tough sell to the recipients of those payments, but on net will probably cause the least economic damage.

An outright default on US government bonds would cause unimaginable chaos in global financial markets.

These bonds are the benchmark for global risk-free assets and are widely used as collateral for trillions of dollars of loans and other transactions.

However, there is also the question of whether the market will view missed interest or capital payments as a default. Strictly speaking they are, since bondholders are temporarily left short. But typically, countries default when they run out of funds, not for technical-legal reasons. Hence it will be a different type of default, but with extremely unpredictable consequences.

If investors draw this distinction, a market catastrophe can be avoided. But the uncertainty will still be large if investors wait to see how others react.

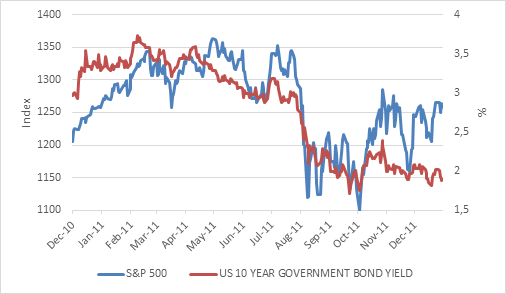

Finally, there are various contingency plans in place, across the US financial system, but none have been tested. The last time the debt ceiling stand-off went down the wire was in mid-2011. Equities fell sharply, as investors were on edge given the recent global financial crisis in 2008, a tepid economic recovery, and an unfolding debt crisis in the Euro area. US long bonds rallied, despite S&P stripping the US of its coveted AAA credit rating. A key difference in relation to today, however, is that monetary policy was extremely accommodative with interest rates near zero.

Markets in 2011

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Cool heads needed

Coming back to the introductory point on unpredictability, the debt ceiling presents a very difficult set of potential outcomes for markets to price in. We know that something will happen in the next month or so, but what exactly will happen is anyone’s guess.

From the point of view of the rand, for instance, you could make the case that the dollar will strengthen because investors normally buy the greenback in times of anxiety. You could equally argue that since the debt ceiling is a uniquely American phenomenon (and a really bad way to run a country’s finances at that), the dollar should weaken if there is no resolution, particularly if the Fed responds by cutting rates.

As with the rand slump of the past few days, investors will require cool heads.

Responding after the fact, for instance by rushing funds offshore now doesn’t help much. In fact, doing so typically does more harm than good.

If your investment horizon is measured over years, day-to-day market moves are best ignored even if they generate big headlines. And despite all the inherent uncertainty, people still need to put their money to work to grow or preserve wealth relative to the ongoing increase in the cost of living.

The key is to have a portfolio that is diversified so that it can withstand any number of outcomes. Because if there is one thing that we’ve learnt over the past few years, it is that unpredictable events happen almost with predictable regularity. Usually, the worst doesn’t happen, and the market impact is short-lived.

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.