Russian policymakers are debating whether to declassify more data as the Kremlin’s drive for secrecy leaves even seasoned observers struggling to make sense of the country’s economy.

Elvira Nabiullina, Russia’s central bank governor, is leading a push to roll back most of a decision to make reams of economic data classified, taken in the early weeks of last year’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, according to three people familiar with the matter.

The Kremlin, which has yet to approve the initiative, has justified withholding information on a wide range of economic statistics as a necessary defence against western sanctions. The classified data sets include important indicators such as foreign reserve holdings and export figures. Russian companies are allowed to keep “sensitive” results secret.

Nabiullina said last month that the country needed to disclose more data for markets to grow. “We need to go back to proper disclosure, with a few exceptions, so investors can invest in securities,” she said.

The central bank said on Saturday that “many authorities share our opinion that we should return to data openness,” adding that it was carrying out consultations with the government on the matter.

“The lack of publicly available statistics affects the quality of analysts’ and researchers’ work,” the bank said. “The Bank of Russia advocates restoring the publication of financial statements, except for the indicators that increase the companies’ and the economy’s vulnerability to sanctions risks.”

The debate highlights the extent to which economic data have become part of Russia’s information war accompanying Vladimir Putin’s offensive in Ukraine — and the west’s efforts to slow it down.

Addressing his economic cabinet on January 17, the Russian president proudly declared Russia had weathered the worst of the sanctions.

“The real dynamics turned out to be better than many expert forecasts,” said Putin. “Remember, some of our experts here in the country — I’m not even talking about western experts — thought [gross domestic product] would fall by 10, 15, even 20 per cent.”

Analysts agree that Russia’s economy has fared better than expected, but Putin’s rush to classify most economic data has left them with little to go on other than his triumphant statements — and has even tripped up the Russian president himself.

Classified budget spending has increased by more than 40 per cent to $95bn compared with prewar planning of $54bn. Russian foreign trade data have disappeared entirely.

The uncertainty around Russia’s data has muddied the economic picture so much that the country’s capacity to absorb the sanctions has surprised even policymakers with access to classified figures, according to three people familiar with the matter.

“The opacity of statistics creates problems even for those inside the system,” a senior Russian central bank official said. “The economic wing has access to the hidden macro data but corporate statistics are sometimes an issue.”

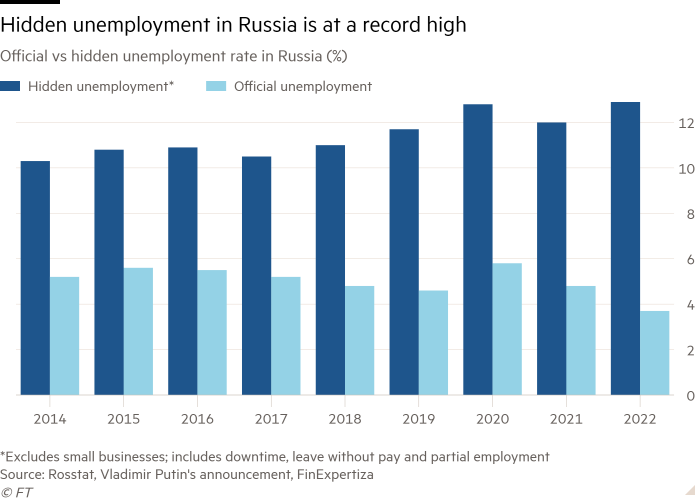

Even figures that are technically correct can mask broader problems. Last week, Putin said Russia had “preserved stability” on the labour market and hit record-low unemployment, below 4 per cent.

Putin failed to mention, however, that hundreds of thousands of workers have fled the country since the invasion began, while 300,000 men who were conscripted into the army now qualify as employed. This might improve the numbers, but it does little for the health of the labour market, according to Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Hidden unemployment, including downtime, unpaid leave and partial employment, hit a record of 4.66mn people in the third quarter of 2022, growing by 7.5 per cent year on year, analysts at consulting network FinExpertiza wrote.

To find the missing data, foreign and domestic analysts resort to creative ways of cross-checking. “We started to use alternative indicators to trace exports and imports dynamics: fiscal data on imports’ VAT, trade statistics of Russia’s external counterparties, shipping data,” said Sofya Donets, chief Russia economist at Renaissance Capital, a Moscow investment bank.

But not everything can be restored. “The lack of public companies’ and banks’ disclosure is a bigger issue.”

The Kremlin said the western sanctions had made it imperative to limit public disclosure.

“There is a hybrid war being waged against Russia, including economic warfare. So in those conditions it is completely natural that we are classifying this data,” Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s spokesperson, told the Financial Times. “Everyone who needs to know, everyone who is part of the economic policymaking process, has access to the whole range of data, statistics and so on.”

Putin’s strict social distancing policy during the Covid-19 pandemic and his increasingly obsessive focus on alleged security threats have left him reliant on a dwindling circle of hawkish advisers and kept his economic team at arm’s length, two former senior officials said.

“All these guys are telling him what he wants to hear. That’s why he makes bad decisions,” a former senior official said. “Everyone is lying to him.”

Putin regularly receives reports from his top officials on the economy, according to his spokesperson. “Any assertions that he receives distorted information are incorrect. He has all the information, he has economic cabinet meetings basically every week,” said Peskov.

Longstanding doubts about the quality of Russian statistics first came to a head in 2020, when excess mortality rates outstripped the official number of coronavirus deaths several times over. But Putin used the official figures to declare that the country had beaten the pandemic and returned to economic growth before the west.

The war in Ukraine has only compounded the issue. When the invasion began, Russia’s government statistics agency Rosstat stopped sharing monthly mortality statistics by single-year age group upon request, said independent demographer Alexey Raksha, who lost his job at Rosstat after criticising its handling of Covid data. This data would have allowed researchers to make similar estimates about war casualties using the methods they used to determine the likely real toll of the pandemic.

“Rosstat counts this data yearly, not on a monthly basis, and shares the data on five-year groups upon request,” a Rosstat representative said.

Experts say the disparity between the public data and real economic picture is less stark, allowing it to still capture broader trends.

In September, Putin gave a public dressing-down to a top energy official for suggesting that gas production at Gazprom, Russia’s state-run monopoly, had begun to decline. “Gazprom’s production isn’t falling. You’re just scaring everyone. It’s going up,” the Russian president told Alexander Novak, deputy prime minister — even though Gazprom’s own statistics showed a year-on-year drop of nearly 15 per cent.

By the January cabinet meeting, Putin admitted gas production had indeed fallen by 12 per cent, a figure in line with what Novak said in a late December interview. But in separate comments only three days earlier, Novak had floated a production drop of 18-20 per cent — and gave no reason for the sudden revision.

At the January meeting, Putin said Russia’s GDP had only fallen by 2.5 per cent, a far cry from the up to 30 per cent hit that top technocrats had warned him was possible in a secret presentation a month before the war. Projections by international institutions are not far off, with the IMF, the World Bank and the OECD all placing Russia’s 2022 contraction between 3.4 per cent and 4.5 per cent of GDP.

Much of the blow to Russia’s GDP has been softened by the country’s ramping-up of military spending, which analysts say does not feed into the real economy. “Tanks, missiles and uniforms contribute to GDP positively. But where are they? In Ukrainian fields, rotting,” said Vladimir Milov, a former deputy energy minister now opposing the Kremlin from exile.

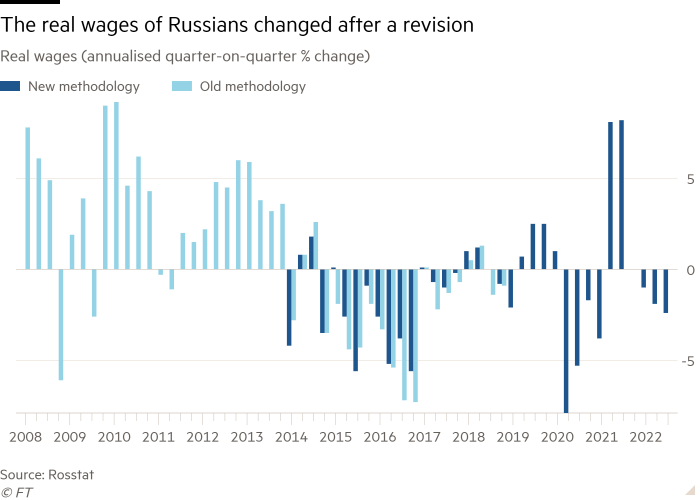

Other inconsistencies are plaguing the few available statistics. Real wage dynamics have become disconnected from retail sales in recent years, according to research by the Institute of International Finance. In 2022, real wages fell by 2-4 per cent, largely benefiting from welfare payments, including those to the soldiers fighting in Ukraine. But retail turnover fell by 9 per cent, according to Infoline projections based on official statistics, likely indicating a bigger hit to consumers.

“It is impossible that people get almost as much as they used to but for some reason spend significantly less,” said Milov.

Some experts also point to Russia’s frequent retrospective revisions to statistics, such as adding dachas, Russian country homes, to construction figures. “These are small changes . . . which do not change the big trends but always work towards improving the indicators,” said Natalia Zubarevich, an economist at Moscow State University.

Rosstat said that such changes are “natural” as the statistics agency seeks to “accurately” reflect any changes that occur in the economy.

Given the opacity of the Kremlin’s decision-making, one senior official expressed scepticism that the policy of secrecy would be rolled back anytime soon: “We are in negotiations and hope they will listen to us, but cannot be sure it will work out.”

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.