The tragedy on Wednesday in which 27 men, women and children died trying to reach the English coast from France very nearly played out in just the same way a few days earlier. A group of young Afghans were led out to sea in the middle of the night by a man they had just met. After several hours, in the middle of the Channel between northern France and southern England, the boat’s engine cut out.

The 21 people squeezed into the small inflatable began to panic. After another four hours waiting in the bitter cold, as they tried desperately to remove the water that had started lapping at their ankles, a woman began hyperventilating.

“We believed we were going to die out there,” says Ahmed Khan, a 24-year-old, whose arm was broken during the failed attempt to cross the Channel. Those onboard were eventually found by a rescue boat and taken back to land — adding to the more than 7,800 asylum seekers this year to have been rescued by patrol boats, lifeboats and other vessels in the Channel.

Will they attempt the journey again? “We will go out again as soon as we can,” says Khan, an Afghan who arrived alone in Calais one month ago.

“What can I do? I have no other option,” he adds, referring to the violence and persecution he says has erupted in his hometown of Logar in eastern Afghanistan since the Taliban took control over the country in August.

Since the deaths on Wednesday, which have shamed and shaken politicians on both sides of the Channel, the French and British governments have been bickering over how to prepare a workable response to the crisis.

An international meeting to be convened by France in Calais on Sunday for British and European ministers responsible for immigration was supposed to map out an urgent way forward. But the intractability of a 25-year-old migration crisis was underlined on Friday when France angrily withdrew its invitation to Priti Patel, UK home secretary.

French officials described as “unacceptable” a letter from Boris Johnson to President Emmanuel Macron in which the UK prime minister called for French and British reciprocal maritime patrols in each other’s territorial waters and for the thousands of asylum seekers who reach English shores to be returned to France.

Paris objected to the contents of the letter, which challenged French sovereignty, but also the way it was made public in what the French see as a transparent attempt to secure domestic political advantage for Johnson.

Anglo-French relations have in the past few months been at their lowest ebb for several decades in the aftermath of Brexit, with disputes bubbling over trade, deliveries of Covid vaccines and fishing licences for French boats, as well as immigration.

On migration, London and Paris agree on an aggressive rule-of-law approach to the problem, with both Johnson and Macron condemning the people traffickers who are said to earn millions of euros a year by charging would-be asylum seekers for help in extracting them from their home countries and ferrying them across Europe to their desired destinations.

Both leaders are looking over their shoulders at vocal anti-immigration critics in the rightwing electorates of their respective countries. And both have emphasised the need for crackdowns rather than reforms to the asylum systems — a path recommended by human rights groups to make it easier for refugees to apply for entry to their destinations from abroad, removing the need for smugglers.

With an eye on the presidential election less than five months away, Macron is eager to show those on the right that he is as serious about immigration as some of his rivals, including the far-right Rassemblement National leader Marine Le Pen, and the newly popular anti-immigration polemicist Eric Zemmour — one of whom he could meet in the second and final round of the election in April if current opinion poll rankings hold steady.

The problem is that cracking down on people smugglers and removing camps full of migrants from the French coast has been tried repeatedly and shows no sign of working. One reason for the sharply rising number of dangerous Channel crossings by small boats in the past couple of years is that both governments worked together to secure the Channel ports and the Channel Tunnel to prevent people stowing away on trucks and in ferries. The people smugglers, and those seeking to get to the UK, are quick to adapt to changing conditions.

The politicians on both sides “prefer to deal with this using police, which is their choice, it’s their political orientation, but you can see that it doesn’t work”, says Pierre Roques, co-ordinator of the Auberge des Migrants, an NGO working with displaced people in the Calais region. “These policies are short-term [because] politicians are thinking about their mandate but they lack any vision.”

A common enemy

On the day of the latest boat disaster, 780 French police officers were monitoring the coastal beaches between the Pas-de-Calais and the Belgian border. Nonetheless, 757 people successfully completed the trip by boat from France to the UK. Winds were light and conditions relatively favourable.

In mid-morning at Dover Harbour, the closest point in England to France, in temperatures only just above freezing, groups of asylum seekers picked up at sea walked slowly up a gangplank towards checks by Border Force officials and buses waiting to take them on to temporary accommodation. All were shrouded in light blue blankets, while some carried children in their arms. A few children arriving were unaccompanied.

Some days the numbers have been even higher — 1,185 people, a record for the current surge in arrivals, made the trip on November 11.

Small boat crossings started to become a semi-regular method of clandestine migration in 2018, according to local UK charities. Though initially the journeys were few and far between, the number and scale has increased rapidly during the past two years.

Calculations made by media organisations based on Home Office information show that up to November 25, at least 26,611 people had made the crossing during 2021, already more than three times the 8,461 total for 2020. However, for the year to June 30 asylum claims in the UK were still 4 per cent down on the same period a year earlier, as the tougher Anglo-French security measures reduced the numbers arriving in the backs of trucks or hidden on trains. That effect has been especially marked since 39 Vietnamese citizens were found dead in the back of a smuggling truck in Essex in October 2019, which had travelled from Belgium.

The pandemic also led to sharp falls in truck, train and car traffic between the UK and mainland Europe.

The sheer volume of small boat migration has in recent months started to push up the overall numbers of applications received in the UK — the 15,104 claims in the July to September quarter were 60 per cent up on the figure for the same period of 2020. Yet, the UK continues to receive only about a third as many asylum applications annually as Germany, fewer than half the number that France does and fewer than Spain. This is because fewer displaced people ever get to the UK.

The calculations about travel routes are made clear by talking to Abdul, a 26-year-old who arrived in Calais six days ago from Iraqi Kurdistan via Turkey and Italy, who says he would have been willing to travel by truck, but “the problem is they have X-rays now”. He adds that a cousin in Kurdistan paid £1,000 for him to take a boat across the Channel after it became dangerous for him to remain at home. He has tried this route twice unsuccessfully and says he will attempt the journey again in the next few days if the weather conditions improve. The agreement many people have with the smugglers is that if they don’t make it first time — usually because police stop them at the beach — they can try again without incurring extra cost.

The smugglers’ use of makeshift inflatable boats, adapted to squeeze more people on and often less seaworthy than normal vessels, is part of an evolution in their tactics in the past year as operations have become increasingly professional. They have used a wider range of beaches even though departures from the coast west of Calais result in longer sea journeys and greater risks. UK authorities say that smugglers arrange large numbers of simultaneous launches on some days, in the hope of overwhelming the French authorities.

Politicians on both sides of the Channel have united around a common enemy: the smugglers. But local groups say the aggressive pursuit of these criminal organisations deflects attention from the lack of safe avenues to apply for asylum and the increasingly violent policing of the border, both of which leave displaced people with little choice but to take more dangerous routes.

“The smugglers go hand in hand with the border, they are the mushrooms that grow with it,” says Roques. “It is instead necessary to suppress their source of income, to fight against people having to risk their lives to cross the Channel.”

‘Inhuman and degrading treatment’

Many of the displaced people in the camps say they have had limited contact with the leaders of smuggling groups, who often send in young workers to warn members of the camp about the timing of a boat’s departure and help ferry them to the beach, like runners in drug-dealing gangs.

Since the Calais “jungle” refugee camp was dismantled in 2016, the displaced people are spread across smaller encampments dotted between Calais and Dunkirk, ranging in size from several hundred to between 1,000 and 2,000. Though these camps have had a steady stream of Iraqi, Kurdish, Syrian and Sudanese people for some years, more recently there has been a rise in arrivals, according to those at the camp, of Afghans fleeing the Taliban.

The people in these camps are separated broadly between those with the means to travel by boat — which costs anywhere between £500 and £3,000, according to several asylum seekers — and those who have no money and are planning to chance their luck by sneaking on to a lorry.

At camps around the Auchan superstore in the town of Grande-Synthe, about 1,500 mainly Kurdish and Afghan people gather in tents. Family members had helped many of them pay to make the journey to England.

A teenage boy arrived in one of these camps on Thursday afternoon, originally from Egypt, dressed in smart, clean clothes and carrying a suitcase, but unable to speak a word of French or English. Close to tears, he spoke quietly on the phone in Arabic to his brother, who was calling from Peterborough in the UK and had paid for the young man to take a boat across the Channel in the next few days.

Roques says that he is increasingly worried about the living conditions and “inhuman and degrading treatment” of those living in the camps. The police come every other day to clear the camps, he says, often confiscating people’s tents, blankets and clothes, and using pepper spray on people who refuse to move.

There are many reasons why people across the camps are hell bent on making it to the UK in spite of the dangers: many have relatives there and already speak good English, others believe the opportunities for work and the quality of life are much better, and have heard that the British are less discriminatory.

A more recent factor is that with Brexit, the UK has now left the Dublin convention whereby asylum seekers are supposed to be processed in the first country they set foot in, meaning the UK can no longer justify refusing asylum to people on the grounds that they arrived elsewhere in Europe first. Some of the displaced people, who faced a grim reception when they arrived in countries such as Malta, Italy and Serbia, are aware of the UK’s new position and see it as the only place they could start over.

Marguerite Combes of the migrant support charity Utopia 56 says that people will continue to “die in the middle of the sea or on a truck” trying to get to the UK. “We have to allow people who need to travel between the countries [to do it] in a safe way. That is the only solution.”

Given the determination of the displaced people, many of whom are facing equally perilous situations in their home countries, several NGOs and local officials are calling for a “humanitarian bridge” to be set up between the UK and EU countries, whereby people are able to apply for asylum via safe routes from centres located across Europe.

Back at the Grand-Synthe camp, Ahmed Khan explains that he lived in London for two years but returned to Afghanistan in 2018 after a relative was killed. More recently, life had been made unbearable by the Taliban, he adds.

“If I die here or I die back in my country it’s no difference to me,” he says. “England is my only hope.”

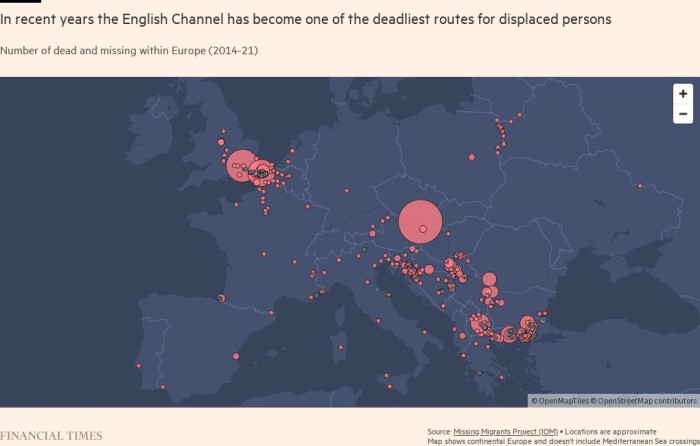

Data and visual journalism by Federica Cocco and Christopher Campbell

Additional reporting by Victor Mallet in Paris

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.