“The streets of Vienna,” wrote Karl Kraus, “are paved with culture, the streets of other cities with asphalt.” Even Kraus, a contrarian essayist and bitter critic of his home city’s bourgeois self-satisfaction, could not entirely disparage the depth and variety of Vienna’s early 20th-century scene.

Of course, we are all familiar with the Mozart and the Mozart Kugeln, the opera and the art, the Sachertorte and the Strauss, central Vienna’s Baroque streets and the queues outside the Café Central. The guidebooks are stuffed with galleries and candlelit concerts in over-gilded churches beneath putti-painted domes.

But perhaps Kraus’s point was that this is a city which also wears its culture on its streets, in its stones and its shop windows, in the bamboo-framed newspapers hanging in the coffee houses, the retail interiors that would never have survived in any other city, and in the architecture itself, often surprisingly radical. Vienna’s paradox is that its bourgeois conservatism has preserved layers of radical intervention and experiment in a sedimented city displaying in its strata the greatest fossils of modernism and beyond. Like shells and sponges cast into a slab of marble, they coagulate to create a coherent and seductive surface.

Take, for instance, the former Goldman & Salatsch store (also known as the Looshaus after its architect Adolf Loos) on the Michaelerplatz. There, right opposite the sprawling rococo mass of the Hofburg is this elegant building, its base clad in luxurious grey-green marble, its solid Doric columns reflecting back a bit of the classical grandeur of the palace. When it opened in 1912 it caused an outrage. A cartoonist compared it to a drain cover, and its unornamented windows were likened to a woman with no eyebrows. Looking a little harder you can see that its stripped simplicity was clearly a riposte to the rococo royal fancies opposite, but it looks dignified and appropriate. It is now a bank, still accessible, still wonderful.

Or you might look at the Retti candle shop. Designed half a century later by Hans Hollein (who once said “everything is architecture”), this little metal storefront with its phallic window (critic Charles Jencks called it “the smallest great building of its time”) is a perfect piece of mid-60s pop. It is cool, gorgeously made, apparently disposable and yet, incredibly, still there, in the Kohlmarkt, bang in the middle.

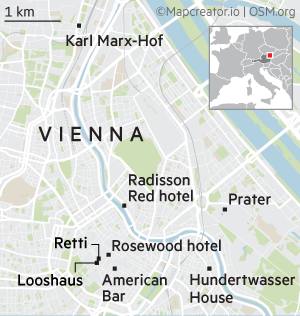

Or, perhaps, you might like to visit the kitsch, bad-trip nightmare of the Hundertwasserhaus, a psychedelic, Gaudí-esque adventure in outsider art and queasy rebellion by Friedensreich Hundertwasser, an artist whose brilliant “Mould Manifesto” railed against the tyranny of straight lines. And finally you might like to visit buildings by Zaha Hadid (one housing project is right next to an incinerator decorated by Hundertwasser in Spittelau), from early in that prickly genius’s career when no one else would go near her work, or perhaps walk around social housing estates such as the 1920s Karl-Marx-Hof in Heiligenstadt, a reminder of an era when Red Vienna looked like the model of the socialist metropolis. Vienna perfected the historic city that appears conservative and ultra-bourgeois but is constantly enlivened by radical and brilliant new interventions.

It’s a good time to visit, during the hiatus between a lazy summer and the strangeness of a city so in thrall to Christmas that it becomes a garish landscape of tourist kitsch and enforced Gemütlichkeit, studded with so many festive markets that they seem to join up into one mass. And new hotels are springing up at a surprising rate. The latest and most desirable is the Rosewood, a slick but discreet operation in the historic centre. Situated to one side of the Peterskirche, a domed Baroque church squeezed into a tight square, it occupies the former HQ of Erste Group Bank, an imposingly white slab of Viennese iced-cake architecture.

One part of the building was once home, of course, to Mozart. With only a small side entrance and no real lobby or front desk, the space is all rooms — gorgeous rooms with views on to the city’s swishest shopping streets. The interiors are embroidered with Backhausen fabrics (the firm that powered the fashions of the Vienna Secession) and fin-de-siècle motifs, and furnished with fine selections of books, about Loos and Schiele and, of course, Mozart.

If there seems very little public frontage below, the real representational space is up top, where a rooftop restaurant and a small (and very heavily booked-up) cocktail bar on a terrace offer views over the city’s domes and spires, snug amid the dozens of rooftop angels and Atlases which appear to be supporting all the city’s ceilings.

For a change of scene (and for something much cheaper), you only need a 15-minute stroll to the new Radisson Red, just across the Danube Canal. If the Rosewood sits amid the fragments of the greatest moments of modernism set into the historic streetscape, the Red has its own little landmark opposite. Otto Wagner’s Schützenhaus, a former lock house on the canal from 1908, is an exquisite work, clad in stone and dark blue tile with a wavy tile motif. It now houses a little fish restaurant.

The hotel itself is a flush-fronted modernist block, with big windows overlooking the canal and a rooftop bar in a funky little greenhouse. This bar is a more raucous affair than the Rosewood’s delicate crow’s nest, a booming beat setting the rhythm for a post-industrial night above the graffitied walls of the subdued canal and the fast-redeveloping cityscape of the north of the capital. It is also a fine base for wandering around Leopoldstadt, the neighbourhood that Tom Stoppard used as the title and the central motif of his latest play, just opened on Broadway.

Leopoldstadt, Vienna’s 2nd district, is a grid of streets that once housed much of the city’s Jewish population. The site of unimaginable trauma and destruction from Kristallnacht and on through the war, it suffered years of relative neglect but is now being repopulated by businesses, bars, design galleries and small, hip restaurants and cafés (most notably in the Karmeliterviertel neighbourhood).

It feels like a piece of city that is still lived in, prior to total gentrification, still an intriguing, less touristy contrast to the quaintness of the historic centre. Not too far away, of course, is the Prater, one of the world’s oldest amusement parks, a strange and sometimes surreal landscape of leisure, with its own quirky architecture spanning everything from Art Nouveau to 1970s utopian modernism (including the Republic of Kugelmugel, a micronation positioned in a wooden sphere).

There is no fee to enter the Prater. You can wander amid the attractions and the beer gardens as a flâneur. It is, in its way, a microcosm of the city, which is itself an architectural fun-palace, a place of almost infinite interest, but one in which it is often the smallest things that are the most intriguing.

Forget, for a while, the vast halls of the galleries, the Baroque palaces, the opera and the churches. Wander, instead, into Knize, Adolf Loos’s tailor, for whom he designed an exquisite shop in the Graben which is still almost exactly as it was in 1909. Perhaps be seduced by a shirt in the warmth of its veneered interior, or have a cocktail in the same architect’s American Bar around the corner in a quiet lane, Kärntner Durchgang.

Its comfortable booths sit in a cool, dark, marble and mirror-lined interior beneath a marble coffered ceiling, the tiny tables illuminated to give an eerie uplit glow. It is, in my opinion, the greatest room in modern architecture and it suggested another way forward, a modernism of grain, reflections and depth, and a suggestion of the infinite in the intimate.

Or you might have a coffee in one of the places so perfectly preserved from the 1940s and ’50s that you feel you are in a film set; Hawelka, Aida, Landtmann, Prückel, all excellent and surprising survivals. In very few cities are the best, the most engaging and the most enchanting experiences available for the price of a coffee or a piccolo of beer.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic

Details

Edwin Heathcote was a guest of the Rosewood (rosewoodhotels.com; doubles from €550) and the Radisson Red (radissonhotels.com; doubles from about €150). For more on visiting the city see wien.info

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Stay connected with us on social media platform for instant update click here to join our Twitter, & Facebook

We are now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@TechiUpdate) and stay updated with the latest Technology headlines.

For all the latest Business News Click Here

For the latest news and updates, follow us on Google News.